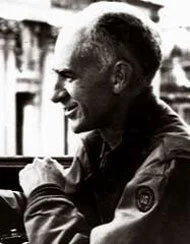

Ernie Pyle

1966

By Vicki Adair

When Ernie Pyle enrolled in Indiana University in 1919, he signed up for a journalism course because he thought it would be a “cinch.” The man destined to become one of the great war correspondents had no idea what he wanted to study. At the time, his only concern was getting far away from anything having to do with farming.

Born August 3, 1900, near Dana, Indiana, Pyle was an only child who disliked nearly everything about the farm on which he was raised. He was a good student, but his desire to leave the farm almost cost him his high school diploma. He longed to follow a friend and join the Army before graduation, but his parents insisted he finish school.

After high school Pyle joined the Naval Reserves, hoping to get into combat, but the Armistice was signed shortly after he joined, so he headed to Indiana University instead of the front. He spent four years working on the school paper, the Daily Student.

In 1923 he was offered a job as a reporter for the La Porte Herald, which he accepted, leaving I.U. without a diploma.

As a cub reporter, Pyle was initially described as “unimpressive” by the Herald’s editor. But he managed to learn the ropes of the newspaper business, and within a few months moved to the Washington Daily News.

He worked first as a reporter for the News, but was soon asked to write headlines and copy edit — a desk job he soon grew to hate. It was during these days at the News that Pyle met and married Geraldine (Jerry) Siebolds, a civil service worker from Minnesota.

Within a year Pyle’s restlessness had become nearly unbearable. He and Jerry took $1000 they had saved, quit their jobs, bought a car and some camping equipment, and set out to see the United States. Ten weeks later they arrived in New York City broke, hungry, and with the car in bad shape.

Pyle got a job almost immediately, working nights at the Evening World, eventually moving to the day shift at the New York Post. But by 1928 he had decided it was time to move on again, and he and Jerry found themselves back in Washington, D.C.

The enterprising Pyle created his own job back at the Daily News — aviation writer. This eventually became an aviation editor position and extended to the entire chain of papers owned by the News’ owner, Scripps-Howard.

Unfortunately for Pyle, his competence put him in line for the job of managing editor of the News, a position he assumed in 1932. He disliked the desk job and being away from the reporting he loved. He was “saved” by an illness in late 1934 which sent him to Arizona to recuperate. During the trip he wrote several articles about his travels. When he returned to Washington, a syndicated columnist was ill, and Pyle used his travel pieces to fill the hole. He soon convinced the Scripps-Howard powers that he should abandon the editor’s desk and become a roving reporter.

The first Ernie Pyle column appeared August 8, 1935, and for the next five years he and Jerry traveled from Alaska to Hawaii to South America as he wrote human interest features.

Pyle’s column achieved a nationwide following when United Features syndicate began selling it to papers outside the Scripps-Howard chain in 1938. But his largest audience wasn’t reached until the war years, when Pyle’s column was seen in more than 200 newspapers across the nation.

Jerry was installed in a new house in Albuquerque, New Mexico, when Ernie Pyle went off for his coverage of the London Blitz. But personal problems — Jerry’s mental health was not good — brought him home soon after. The Pyles were divorced in 1942.

That same year Ernie Pyle went to the front in Northern Africa. He followed the infantry to Sicily, Italy, and France. During this time his reputation and popularity were growing. His columns dealt with soldiers, rarely the details of the battles they fought. He named names, and thus made friends of the soldiers and their families.

In addition to his professional acclaim, his personal life was improving. He and Jerry were remarried by proxy during the North African campaign.

When Pyle rode into Paris August 25, 1944, he had been overseas 29 months, nearly a year on the front lines, and had written 700,000 words of copy. He said, “The hurt has finally become too great…if I had to write one more column, I’d collapse. So I’m on my way.”

He didn’t rest very long in the United States before he headed to the war in the Pacific. He was with the Army’s 77th Division on the tiny island of Ie Shima. On April 18, 1945, Pyle was headed to the front lines when he was killed by a Japanese gunner.

Journalistic Contributions:

From that first “cinch” course in journalism at Indiana University, Ernie Pyle went on to become what many have called the greatest war correspondent of all time. He probably wasn’t the best writer, nor did he have the best grasp of the “big picture.” But the farm boy from Dana won the hearts of Americans because he wrote about the men fighting the war, not the war itself.

His talent lay in telling the story of “G.I. Joe” — someone’s son, brother, or husband. He became the friend of the fighting man, from the lowliest private to the highest-ranking general. For these efforts to humanize the war, Pyle won a Pulitzer prize in 1944.

Pyle’s journalistic style was developed during his years as a roving reporter when he brought the world into his readers’ living rooms. Pyle said he traveled for other people and wrote their letters home. It was this letter writing ability which made him so popular as a war correspondent.

The extent to which Pyle’s writing touched his fellow Americans was shown in their response to his death. The nation mourned him. President Truman issued a formal statement. Senator Carl Hatch of New Mexico, Ernie’s adopted state, said that “no Japanese bullet can kill the spirit which will live in his writings.”

Ernie Pyle wrote no books, but his columns have been compiled in several volumes: Ernie Pyle in England, Here is Your War, Brave Men, Last Chapter, and Home Country.

Other Contributions:

Ernie Pyle once said that everything he knew, felt, thought, saw, read, or dreamed about went into his columns. His years overseas and the years spent on the road while he was a roving reporter kept him from becoming involved in other things not related to his job.

But he contributed to society beyond the words he wrote. John Hohenberg, in his book on foreign correspondents, described that contribution best when he said:

No reader of Ernie Pyle’s World War II pieces for Scripps-Howard newspapers could fail to be moved by his personal involvement with G.I. Joe, a powerful factor in creating a toughened national morale.